Memory is a kaleidoscope of bits and pieces. We don’t recall a continuous storyline of life, as in a book or movie; no – we recall fragments, incomplete pictures, partially remembered incidents. But sometimes a string of fragments tell a story. Recently during a bad cold, in a half-awake, half asleep state in the early hours, a few fragments of memory reminded me of a talent I once thought I had.

Fragment one: Green Lane Junior School, age 9 or 10. We got an in-class assignment to draw something. Can’t remember specific instructions, except it had to be a freehand drawing and not a tracing. I drew a kangaroo. It was the talk of the class: so lifelike they all said. The teacher however gave no praise at all, which left me disappointed, but he left my drawing on the pinboard for several weeks. I got the idea I could draw.

Fragment two: Acklam Hall Grammar School, Mr Robertson’s art class, drawing a still life. In preparation, he’d given us a lecture in the use of a pencil, emphasising light delicate work, rather than slashing a thick graphite line with every stroke. We began, and I drew the still life with such light strokes it was almost invisible. As the session progressed, there were giggles and comments from my mates – they thought I was deliberately lampooning Mr. Robertson’s instruction, and anticipated trouble (What, me Sir? No Sir. Just doing what you told us Sir.) But it didn’t happen; in fact I was commended for the work. I definitely thought I could draw.

Fragment three: Another art lesson. In exasperation, Mr. Robertson had the class gather behind him, and watch while he demonstrated sketching a still life. To our astonished gaze, he was incredibly competent: quickly, fluently, the drawing magically unfolded into a stunning sketch. I can recall the chatter in the corridor leaving the lesson, comments like “wow that was amazing – he must be a real artist”. We were extremely impressed. Unfortunately he was unable to impart the skill by which he achieved the result, but I knew he could draw, I recognised quality when I saw it.

Fragment four: An annual school report. Mr. Robertson placed me top of the art class but also wrote: “however, Craig should not consider a career in art.” Ambiguous, bewildering, especially when he said the same thing to my parents at a parents evening. I lacked the confidence to ask for an explanation.

Fragment five: Despite these comments, I chose to study A level art with Mr. Robertson. We were a small group of five or six, and the art room became our personal common room for two years. He encouraged us to use it at break and lunchtimes, and gave us a pretty free hand. One week, only half serious, I created an abstract painting of a sunset in reds and yellows, which drew humorous criticism from my mates, who thought it was a bit of a joke. As I did – I nearly threw it away. But to our astonishment, Mr. Robertson told us it was the finest thing I’d done so far. Why was it better than previous work? None of us knew or asked.

After four years at college I became an art teacher myself. At my first school I was fortunate to have Roy Hildon as my head of department. He was, like Mr. Robertson, a fine artist in his own right. But he was also one of the most skilful teachers I’ve ever known. Over four years he taught me how to teach but also the basic foundations of art, which I hadn’t grasped in either the sixth form or even in four years of college. I began to understand what Mr. Robertson had been trying to tell me those years ago: I was good at copying but not creating – a significant difference (one that, as an art teacher, I found impossible to explain to parents who thought their Johnny or Mary was a brilliant artist). I didn’t have the passion or commitment for hours of study and practice. My drawings lacked fluency and flair. Crucially, I didn’t have sufficient creative awareness or freedom. Mr. Robertson saw a glimmer of it in the red and yellow sun but the sun failed to rise in me as an artist.

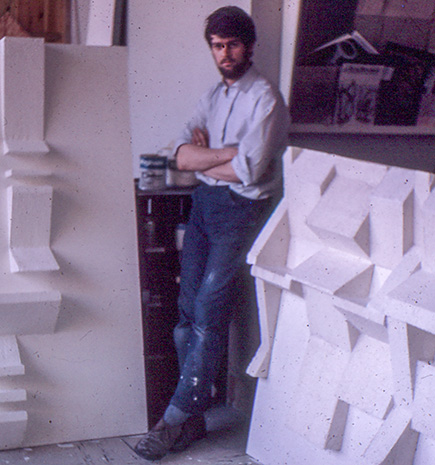

In a previous post ( https://craig-marshall.net/pottering-around/ ) I suggested I’m basically a craftsman – more artisan than artist. This explains the Ben Nicholson-derived reliefs I developed in my final years of college. But unlike Nicholson, I was still dodging visual analysis and draughtsmanship. Well, not wholly true – you may be surprised to hear that those minimalist reliefs of white planes and geometric blocks were the end result of a lengthy, detailed analysis of tree structure, and helped me get my teaching degree – I wan’t entirely hopeless.

Many of my blogs are quite personal, but this more so than most. So if you’re still reading, I remind you that all my posts are a “memo to self”. So where am I going with this? What do I learn from it?

With an exception of the occasional genius, talent isn’t always obvious. Even when identified, competence develops gradually, and talent requires work and effort to flourish. I learn that comprehension exists at different levels. It begins with the superficial (copying a kangaroo) but continues to greater depths (a Rembrandt portrait, a Turner landscape). I’ve enough appreciation of music to enjoy a Beethoven symphony, but a musician sitting next to me has a deeper experience, hearing and feeling things beyond my grasp through a language I haven’t learned. This is obvious in the arts, but true in any branch of knowledge or skill, including maths and science.

It’s also true in matters of faith. Like other talents, some people are born with great spiritual awareness, though it still requires work and effort to develop. My religious belief is different now than at age ten when I was baptised, I hope deeper and more profound. My childhood idea of being good was following a set of rules on a checklist. Prayer was a routine task on the list, but now prayer is a sacred conversation, when I can share my greatest joys, deepest worries, and seek help and comfort.

A talent for spiritual matters is different from others, because, while some seem born with innate capacity, it’s available for anyone just for the asking. If we ask in faith, our Father will help.

4 And when ye shall receive these things, I would exhort you that ye would ask God, the Eternal Father, in the name of Christ, if these things are not true; and if ye shall ask with a sincere heart, with real intent, having faith in Christ, he will manifest the truth of it unto you, by the power of the Holy Ghost.

5 And by the power of the Holy Ghost ye may know the truth of all things.

(Moroni 10:4-6)

A sincere heart, real intent, and faith in Christ is all it takes. Sufficient desire opens the fountain of heaven, but casual, indifferent inquiry is never successful. As with other talents, some find it harder than others, but there are gifted people to lead the way. Prophets and apostles, seers and revelators have spiritual insight and perception far beyond mine. My development in art and teaching moved forward when I listened to guidance from experts. I wish I’d been more attentive earlier. I hope I’ve learned enough to be guided in faith by following the great spiritual leaders appointed by God himself