Discussing Death

In the summer of 1348 a French merchant ship berthed in the port of Melcombe, in Dorset. Unknown to the crew, she carried an invisible additional cargo: Bubonic Plague, which came to be known as the Black Death. From Melcombe it spread rapidly and by the end of 1349 the plague had affected the whole country. Roughly a third of the population of England (and Western Europe) died. It was the worst pandemic in history. The Covid pandemic has raised the spectre of death again, thankfully nowhere near that scale. The focus on Covid related deaths overshadows a figure we tend not to think about too often. The total number of deaths that occur for all causes in England and Wales is roughly 9,800 each week. Consider that for a moment: in this small country alone, over half a million people per year walk through the veil of death. Half a million! In the whole world, around 55 million die each year.

We all die and death is a normal part of life. We prefer not to think about it; it’s not a subject for dinner-table conversation. Yet it’s ordinary and commonplace. We watch it in television shows, we hear it in news media. But when it touches us personally, when someone close to us dies, it becomes extraordinary. It can be emotionally catastrophic and for those who remain, life-changing. In 2018, President Nelson, who is the prophet and president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, mentioned a life-shattering experience thirteen years previous:

“In 2005, after nearly 60 years of marriage, my dear Dantzel was unexpectedly called home. For a season, my grief was almost immobilizing. But the message of Easter and the promise of resurrection sustained me.” (Russell M. Nelson, Revelation for the Church, Revelation for Our Lives, April 2018 General Conference)

Think of it: even a prophet immobilised with grief!

My first significant encounter with death was at age 17. My family was together in our front room, when we saw Pat Atkinson passing the front window on the path to our door. This was unusual and I had a sudden premonition of something badly wrong. She brought news that Arthur Hunter had died in a car crash during the night. Arthur was older than me; a young adult who had been my mentor, confidante and best friend for the past three or four years. Disbelief, shock, gut wrenching emptiness filled me. Needing to be alone, I stumbled out of the house and walked down to the footbridge over the beck at the end of our road. I stopped on the bridge, unable to go further, feeling sick, leaning over the side rail, staring at the swollen stream. A friend came across the bridge, looked at me, stopped briefly and said “you look really ill”. I suppose my face was devoid of colour, as empty as my mind. Arthur was so much part of my life, which was now turned upside-down. We were planning a tour of Greece that year, in his Mini. He was my inspiration, my guiding light, and now he was gone. I was indeed “immobilised with grief”.

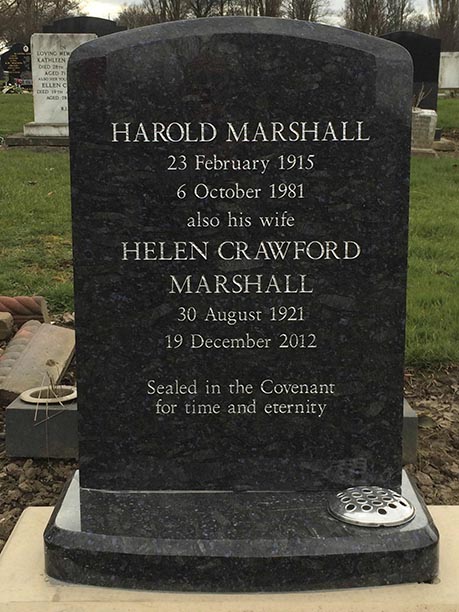

Some years later, on 6th October 1981 I was with my leader and dear friend Dave Cook in the Huddersfield chapel. We were training a small group of seminary teachers. This of course was before the days of mobile phones and instant communication. As we were speaking, out of the corner of my eye I saw a policeman in the corridor, through a window in the classroom door and Dave was beckoned out. I thought it was curious but just continued the discussion. After a minute or two, Dave came back and asked me to join him with the policeman in a different room; my apprehension grew. He said “I think you had better sit down, I’m afraid we have some very bad news”. I was immediately convinced something had happened to my wife; I couldn’t breath, shock set in; all this in fractions of seconds. Gently, I was told that my father had died from a massive heart attack earlier that day. My relief that it wasn’t Barbara was so great, I nearly burst out laughing with the instant remission of my initial fright. I managed to control myself, but even so the policeman must have thought my reaction was unusual. Though it was sad and difficult, I wasn’t immobilised with grief this time. Since then, I’ve had many encounters with death as a Church leader, counselled many grieving families, and conducted many funerals. My own experience has helped.

Now death is in the headlines again with the coronavirus pandemic, although mainly as a statistic, just cold figures. Society as a whole prefers not to think about the nature of death too deeply. It’s the great unknown, the ultimate enemy. Past generations were more closely acquainted with death. In 1800 the average life expectancy was 40 years; today it’s double that at 81. A big factor is the reduction of infant mortality. In the 16th century around 25% died before reaching the age of 5, and 40% died before reaching adulthood. Many families, perhaps a majority, experienced the bitter sorrow of untimely death. Perhaps because of this, faith was more widespread in those days and helped many grieving households. Today, an extraordinary thing for me is that, even in the middle of a world pandemic, how little discussion is heard about the attributes of death and the nature of existence. Where do we come from? Why are we here? Where do we go to? Is death the end?

To me, these are the most important questions we can ask, yet fewer and fewer people seem to give them serious thought and even avoid discussing them. Well, I’ve spent a lifetime giving them serious thought. Central to my faith is that we are eternal beings; we existed before this life and we continue to exist after it. I have no doubt about this. Death is a separation of our spirit from our bodies but because of Jesus Christ there will be a resurrection, spirit and body to be reunited eternally. As he said to Martha:

“I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live:

And whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.” (John 11:25-26)

Jesus Christ is my Saviour and Redeemer; his atonement and resurrection gives meaning to life and a reassuring perspective of death. That doesn’t mean we don’t grieve when loved ones die, we will miss them terribly for a time, but it helps us cope. Prayer and pondering have led me to my faith. Jesus Christ and his Church fill my whole life, define my existence and the person I am. I just wish that more people would give more thought, pondering and prayer to the fundamental matter of life and death.