In June of 1953 at six years old I had no interest in the Coronation. Couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about. Only one house in our street had a TV—and most of the street crowded into that small, semi-detached council house. Favoured friends squeezed into the sitting room, within actual sight of the tiny, black-and-white, grainy picture, others listened from the dining room and kitchen. Others gazed through the open windows. I was part of the crowd for a very short time, but slipped away, totally bored.

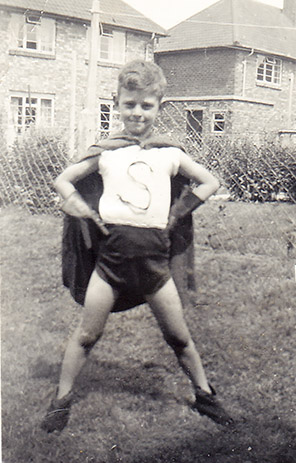

I was preoccupied with far more important things—saving the world in fact—I was obsessed with Superman. Don’t remember if I met him in a comic, or was taken to the cinema, but he was my hero. After all, Superman can see through walls, bend steel girders, and fly! He rights wrongs, defends the weak, captures the bad guys and makes the world a better place. True, he gets dangerously feeble when exposed to Kryptonite but I hadn’t come across any Kryptonite in our neighbourhood, so I pestered mother until finally she made me a Superman outfit from bits of old curtain. To my six year-old eyes it was magnificent—the real thing. In the photo above I am indeed the mighty Man of Steel!

So I was master of the universe with superhuman powers. One problem: when I tried to fly, it didn’t work. Why not? I had the right uniform with the all-important S on the shirt. Must be technique I thought, and spent many fruitless minutes running up and down the back garden, leaping into the air with different poses: right hand pointing up, now left hand . . . but always came to earth in an undignified heap.

Now, in case you think this explains a lot about my peculiar personality—strange characteristics you’ve privately wondered about—let me elucidate. I’m pretty sure that secretly I knew I couldn’t fly despite my magic suit. But at six years old, there is always a glimmer of hope, the tiniest spark of belief that just this once magic might happen. At least, that’s how it is in the world of imagination. As adults we forget how powerful childhood imagination can be. Children instinctively like to pretend. Their play can, for a time, create a parallel world of the mind as substantial as the one they stand on. Even for adults, the suspension of disbelief enhances a novel or a movie, as we voluntarily enter a different orbit. Coming out of the cinema or closing the book can be painful as we re-enter the real world with its struggles and challenges. For children imaginary worlds are especially substantial, one reason why fairy stories endure as part of childhood development, and generations of parents still tell the story of Father Christmas.

We instinctively understand this, from observation of children and memories of our own childhood. We also understand the need for caution and protection. If a child was convinced they could fly if they jumped off a bridge, how would we respond. Take them by he hand and say “oh, I know a really high bridge to jump off, let me take you there and help you jump”? Ridiculous; but what would we do? Talk about it with them of course, and help them distinguish reality from make-believe. If they were really determined, we would surely get psychiatric help. (As I write this I remember a bitter experience: a psychotic young adult I knew heard voices in his head. The voices told him he could fly if he jumped off a bridge. He did. I know the bridge, it’s very high. The amazing thing is he survived, but he was badly smashed up. He was a gifted athlete, but he was unable to ever run again.)

I don’t believe what I’ve written is controversial. I’m sure a vast majority of adults recognise the truth of it. I’m therefore dismayed and astonished at much of the nonsense peddled in social media about sex, gender and trans issues, especially concerning children. I stare in disbelief at absurd statements and unsupported claims. I passionately believe we harm children by persuading them that boys can be girls if they want, and vice-versa, which is apparently happening in some schools. To me, it’s the equivalent of helping a child jump of a cliff because they think they will fly, or indeed introducing them to the idea and persuading them they can fly. I sometimes wonder if those who promote trans doctrine with children live in the same world as I do.

Normally, when a condition of the mind is at variance with the physical reality of the body, we regard it as a mental illness that needs treatment—for example, anorexia nervosa and similar eating disorders—or my tragic friend who jumped off the bridge. But over recent years it seems like any issues of sexuality are enclosed in a bubble which is exempt from discussion or rational analysis. We are not allowed questions or debate: certainly the possibility of mental illness cannot be entertained. Closing off a significant element of the human condition like this is surely a troubling development.

Back to childhood where we started: I’m reminded of the famous teaching of Paul in the thirteenth chapter of First Corinthians.

11 When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

There’s a time when fairy stories and Father Christmas cease to be literal (though their priceless metaphorical message may live on). We need to live in the real world and accept that even with a Superman costume, we can’t point at the sky and fly. However, as many of you know, 1 Corinthians 13 is primarily known as a sermon on Christian charity—the pure love of Christ, and in other verses we read these words.

1 Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.

2 And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing . . .

12 For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

13 And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.

This fundamental Christian imperative to love all mankind doesn’t mean we must accept socially fashionable doctrines, often the views of small influential elites. After all, Jesus opposed the Scribes and Pharisees throughout his ministry. But it does mean we accept that others have the right to think and believe as they choose. Passionately, I defend their right to do so. But I expect to be given the same privilege and allowed to express my views without being shouted down. One view I hold dear is that promotion of controversial ideology from the trans community has no place in our children’s classrooms.